About the Author:

Study Comic Reading and Creation in Angoulême and Comic Publication in Brussel; worked with French alternative manga publisher, Le Lézard Noir. Comics's been haunting Ping-Lu for decades and will never end. Reside in Europe but dedicate herself to Asia. IG account: @cases.clubs open to any comments.

“Like common Taiwanese, I have been exposed to the many influences of Japanese culture since I was young. I have always loved to read manga, draw manga when I was a child, and started to read Japanese literature, detective novels when I was older… However, I hate to use any ‘style’ to define a person’s creation, even though this is still a way this world labels other people, which undeniably has profound influences on me. Nonetheless, I still hope that this can be avoided. I am not striving to echo ‘Taiwanese history’ through ‘style,’ and I have never considered the possibility.”—Gao Yan, in an interview at Funker Says in 2019

“Actually, I have had questions; some senior comic artists say our styles are similar to Japanese manga. It feels like an accusation; but if my works were to be placed next to Japanese manga, no one would think my works are Japanese manga. They would even condemn them as Taiwanese comics. When I first came into the industry, I was troubled by this, and wondered whether people really couldn’t see us this way?”—Kiya Chang, in a dialogue at Taiwan Comics Is Not Dead

In Taiwan, when we talk about comics, perhaps due to the high market share of Japanese manga, we often think of pictures consisting of black and white lines, screen tones, and speed lines. With few comics from other countries available in the market, we easily associate this “generalized” style to an entire country. However, regarding the issue of style, can we really define the characteristics of a creator from the perspective of national culture?

In the introduction, Gao Yan briefly answers this question from the standpoint of a creator, whereas Kiya Chang’s question seems to also illustrate the generality which connects “style” with the comics of a country, just like Europe uses “manga” for Japanese comics and “comic” to differentiate American comics; nonetheless, they are all “bande dessinée” in essence, which are a kind of drawn strips. Although every region has its own comics, and perhaps it is out of convenience that they are referred to with their original names. This has also forced the comic cultures of other smaller countries to look for an “overall style” different from the major countries in order to safeguard their own uniqueness (Note 1).

To maintain this uniqueness, style seems to be the first issue faced by creators or related professionals (Note 2), for pictures are the first key factor readers look at to learn more about the work. When we talk about style of picture, or even comic style, it is a complicated concept, because it represents expressive means. It not only involves the means of expressing contents, but also covers the options of visual expressions. In other words, the “style” of an author is in the “entirety” of his or her work, it is “how” the author (and related professionals) create “each and every aspect” of their work.

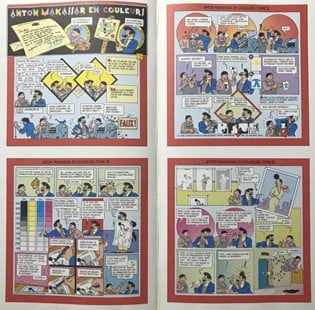

Perhaps it can explain how the overall style of a country is generated; if the country’s industry has popular and existing procedures of production, the works produced industrially will very likely form a similar image, thus making readers generalize or sum up their impressions of the comics into the overall style of the country. Therefore, the expression languages of Japanese manga and American comics are concrete and can be identified easily (Note 3), whereas European comics give the impression of having diverse contents. A work does not just reveal the author’s own creative intention, but is also influenced by direction of edition, limitations of communication medium, and reader engagement, deriving an overall look (Note 4).

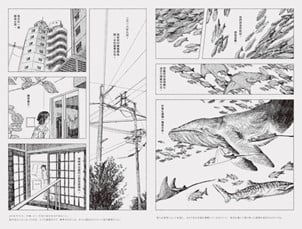

Therefore, once we understand the origin of style, perhaps it is not hard to understand why some readers recognize Taiwanese comics as within the family of Japanese manga, for based on the frames, lines, and screen tones, or even the use of drawing medium, some Taiwanese comic artists are still students of Japanese manga (such as application of manga dip pen or other similar tools, page limits of each chapter, and so on). When the physical conditions (such as painting tools and printing and publishing models) are all like the industry in Japan, possible variations in the presentation of works are limited, and their own uniqueness compromised. Nonetheless, every aspect has its unlimited possibilities and combinations, and it all depends on the choices made by the creator and related professionals. Even with editor’s intervention or under the limitations of printing costs, every author can still create their own expressive forms through design, stroke, light, scenery, and narrative. They can even change their own style in response to different works, like Minetarō Mochizuki or Taiyō Matsumoto.

This is why authors need more variables in creative means to further differentiate with other authors. It is like creating new visual expressions according to different themes, changing drawing tools and procedures, or printing methods to generate feelings. It is also like Hong Kong artist Lau Kwong-Shing’s understanding of style: he was profoundly influenced by mainstream Japanese manga like One Piece in the past, but when he changed his drawing tool from ink to pencil, it created for him a new visual creative model. In other words, when creators and related professionals work hard to give life to works, the works will take on their own styles, and styles are in fact the “creators’ will” (Note 5).

Therefore, trying to depict or identify a country’s overall style seems in vain, for everyone’s creative method is different; even when similar tools or production models are used, there will still be a touch of individuality in the works. In Taiwan, it is even more futile to find a consistent style, because when we understand the factors giving rise to a country’s overall comic style, and then look back at Taiwan’s trying to grasp its own style, its appeal is perhaps not just to highlight its own uniqueness of existence, but also a desire for a matured industry chain. Thus, it is not hard to understand Kiya Chang’s description of readers’ attitudes in the introduction. Some readers dislike Taiwanese comics because a certain production method has become a popular “style” in this less-than-ideal situation where the economic benefit of the industry is immature; if Taiwan shared similar physical conditions of publishing with other countries with mature industries, it would be easier for readers to compare and make own judgements (Note 6).

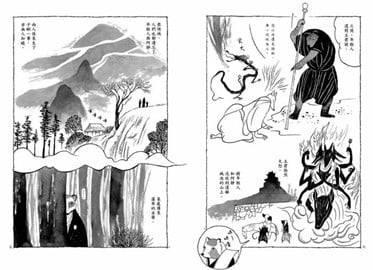

This also proves that, in Taiwan, the developments of realistic inclination referring to real objects and things, and the so-called illustration books and illustration style (different from works drawn with black and white lines), are not groundless. The former directly presents the uniqueness of personal experience and displays the skills and techniques through depicted objects, whereas the latter achieves differentiation by using painting materials unlike the industrialized creative means in other countries. Therefore, Gao Yan’s work, Sukima, instinctively delivered who she is as a Taiwanese due to her creative insistence while she applied techniques or styles similar to Japanese manga, such as the method of storyboards and black and white manuscripts. In addition, Animo Chen incorporates the everyday mottled quality into work The Short Elegy, in which the pictures feature layered and diverse colors give the impression of an “illustration book,” or “illustration,” while also presenting the author’s own unique understanding of pictures.

In conclusion, style involves overall aspects, not just author’s personal expression, but also limitations generated by the activities of publishing. In other words, we cannot simply use the country, publishing system, or even author, to generalize “style,” for every work has its own unique messages within, and every work is an independent entity. Thus, if a creator only thinks about how to use the right method to depict the entirety of the work during the creative process, then his or her work will have the possibility of independent expressions.

Note 1: Because comics have profound connection with national cultures, Europe has seen the emergence of the use of “manhwa” to refer to Korean comics, as well as “lianhuanhua” or “manhua” for Chinese serial pictures and comics; however, these terms are not generally used in discussions.

Note 2: Actually, regardless of whether they touch upon national identity, creative activities all incline to “surpass;” that is, they continually look for other possibilities. Refer to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. In countries with matured or maturing industry chains, even though all professionals do their respective jobs independently, new works and new themes are still being developed and explored. However, style is also related to an author’s habits, and habits are somewhat in conflict with the concept of “surpass,” for an ambitious creator will never be limited by own habits.

Note 3: For example, artist Takashi Murakami’s appropriation of the cute aesthetics in the anime and manga culture as artworks for display or American pop artist Roy Lichtenstein’s application of enlarged colored screen tones of American comics to his works; their works all remind people of comics, but they are not comics.

Note 4: Though there was a model of division work in European comics production process, such as screenwriting, drawing, coloring, and inking, editors had limited interventions. However, over the last two decades, there have also been many small and medium comics publishers that target different genres, giving rise to diverse creative models in the overall industry.

Note 5: Undeniably, when multiple works are compiled under a magazine, a collective way of creation arises, just like how we describe works of Japanese manga with terms like the “Jump school,” or “Garo school,” or the different magazines of European comics that have given rise to the “Ligne Claire” school (Tintin) and the “Style Atome” (Spirou).

Note 6: This is not just in comparison with Japanese manga; Taiwanese Youtuber Li Han has also mentioned in one of his videos that he was stunned to see the similarities between the expressive methods of Richard Mai’s The Black Book published in 1995 and Frank Miller’s Sin City published in 1984.

Original text: https://www.creative-comic.tw/special_topics/117