I was born in the early 1980s. When I was in elementary school, I had a backpack and pencil case featuring images of Garfield. My writing mat was illustrated with Georgie. On the easel I used for outdoor painting were images of Oscar and Marie Antoinette from The Rose of Versailles. And Snoopy and Doraemon graced the covers of my notebooks. I was surrounded by all kinds of comic characters even before I began reading comic books. Comics have quietly penetrated our lives.

It All Began With A Ubiquitous Little Black Dog

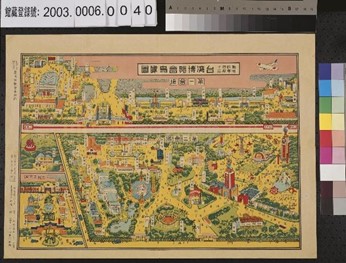

Cheng Li-jung, a historian of Taiwan, mentioned in an article that she and her siblings grew up with a Kodansha-produced black dog alarm clock that her father brought back from a trip to Japan in the 1980s. But she only discovered this little black dog called Norakuro was part of the comic book memory of her father’s generation after she accidentally spotted the same black dog on the aerial view map of the “Taiwan Exposition: In Commemoration of the First Forty Years of Colonial Rule.”

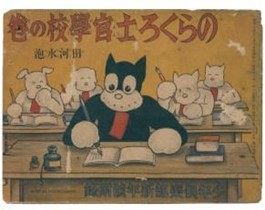

Norakuro, whose full name is Norainu Kurokichi, also known as Corporal Norakuro, is a comic character created by Suiho Tagawa and first appeared in 1931. It was the first comic strip published in Kodansha's Shonen Kurabu, a magazine for teenage boys. Influenced by Disney’s animated films at the time, this anthropomorphized little black dog, the embodiment of the ordinary man, bore a resemblance to American comic characters. The first Norakuro animated film was released in 1933. During wartime, in 1938, it served as a spokesperson to promote and beautify war. The animated films of Norakuro were also screened in Taiwan during the Japanization movement. Norakuro also appeared in other aspects of daily life in Taiwan, such as the abovementioned Taiwan Exposition and even a school-held costume procession. (Chen, 2018)

Norakuro’s journey did not end with the end of the war. Like an ordinary soldier who served in the army, Norakuro also returned to society, started a family, and had offspring. After Tezuka Osamu’s Tezuka Productions launched Astro Boy, the first Japanese-produced animated television series, in 1963, a television series of Norakuro was also broadcasted to households in Japan in 1977. After the creator Tagawa Suiho passed away in 1989, Tagawa’s apprentice continued to work on the comic series until 2013.

A Comic Character Leaping out of the Pages

The Norakuro alarm clock and the historian’s family story show that this little black dog remained such a well-known character across Japan in the 1980s that its publisher rolled out its merchandise. We also understand that through the commodification of comic characters, comics can leap through physical space and time, bridge the gap between generations, and be a part of people’s lives and memories.

As early as the 1930s, Kodansha began producing merchandise of Norakuro and many other comic characters. First published in 1914, Shonen Kurabu was the most talked-about children’s culture magazine in Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period. Taiwanese readers could get hold of the magazine by subscribing to it through money transfer at the Post Office, purchasing it in stores, or borrowing it from a library or a friend. (Yu, 2007) Besides being rich in content, the magazine also came with a variety of paper toys, such as board games, supplements, pictures, papercrafts, or other collectibles, pushing the development of magazine giveaways to the peak since the mid-Meiji period.

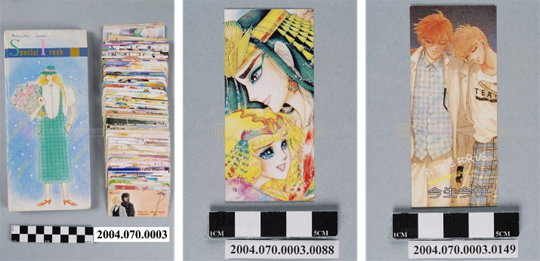

As a beloved comic character, Norakuro naturally appeared in all kinds of free gifts that came with Shonen Kurabu. It could also be printed on Menko cards or other inexpensive toys without official authorization. Thanks to the advancement of printing techniques and lower printing costs in the 1920s, a large amount of printed matter and many paper toys were manufactured featuring images of the most liked comic characters, athletes, or monsters of the time. They were indicators of popular culture among children and adolescents. These toys and comic magazines were later imported from Japan to Taiwan through trade and became part of a generation’s childhood memory and comic upbringing.

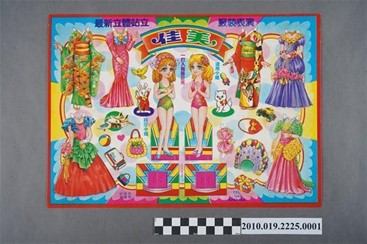

In the post-war era, toys like Menko cards continued to feature the most popular comic characters. Homegrown comic heroes like Chuke Ssu-lang and Chen Ping, created by Yeh Hong-chia, came to be the most sought-after among children in Taiwan. However, in the mid-1960s, the implementation of the Regulations for the Publication of Comic Strips, commonly known as the Comic Censorship, restricted artists’ creativity, impacted the local comic publishing industry, and caused a gap of two decades before the revival of local comics. To evade these regulations, publishers turned to translate or redraw unauthorized comics from Japan after the National Institute for Compilation and Translation began accepting submissions of Japanese comics for review in 1975. Like Japanese comic magazines, local publication Comic King Weekly was sold with free paper toys, while others like Hsiiaomi Comic Weekly featured Japanese comic strips for teenage girls. The pirated editions of Japanese comic books such as Crest of the Royal Family, Glass Mask, The Rose of Versailles, I'm Teppei, Black Jack, and Doraemon also entered the Taiwan market. The local comic publishing industry was subsequently booming again.

Meanwhile, as color television became widespread in Taiwan, local television channels began broadcasting popular animated series such as Science Ninja Team Gatchaman, Mazinger Z, and Candy Candy. Japanese comics and animation thus gained greater prominence and popularity among Taiwanese audiences. They dominated most people’s experience of comics and animation and furthermore influenced local comic artists active since the 1980s. American comic characters and their universes were introduced to Taiwanese audiences through a series of live-action movie or television adaptations of superhero comics such as Superman, Batman, and Spider-Man.

These much-loved foreign comics and animation by Taiwanese readers were naturally commodified into all kinds of products one can think of and entered all aspects of our lives. People of my generation live in an environment full of elements from comic books and animation. From Mickey Mouse, Snoopy, and Doraemon in the early years of our lives to One Piece and Demon Slayer: Kimetsu No Yaiba in recent years, we are surrounded by objects with comic characters or emblems printed on them. What’s more, some comics transcend their graphic nature, with their storylines turned into card games or video games, adapted into movies, television series, or stage productions. Some were even transformed into themed tours to boost tourism, amusement parks that present their universes in reality, or virtual realities through digital technology. Comic stories and characters no longer exist only on paper but are marketed as brands. Besides being read, comics are converted into experiences, interactions, and consumer behaviors and are forming new relations with audiences.

The development of society and technology also influences the integration between comics and media other than books. Simple and inexpensive paper toys were the most common in Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period and early post-war era. But comic characters began appearing on more diverse stationery and everyday items as time passed, even though elementary and junior high school students remained the target market. The materials, forms, and methods of use of these toys, stationery supplies, and everyday items also reflect the transformation of Taiwan society and its industry development. For instance, as Taiwan’s plastic processing industry reached maturity in the 1960s, the previously popular paper or tinplate toys were replaced by plastic toys, such as flat plastic figures made by injection molding.

I Own It, I Share It, I Collect It, and I Identify with It

Jean Baudrillard believed that, in contemporary society, an object exists on two different levels: the systems of denotation and connotation. The former refers to an object’s functional meaning, and the latter focuses on how an object is commodified, personalized, and enters the cultural system so that consumers can express their identities and points of view through this object. In addition to functional purposes, comic merchandise has communication and collection values. With a large market for comics and animation, Japan has a fully developed industry to cope with the varied demands of consumers. Menko cards, trading cards, or video games featuring the trendiest comic characters are important tools that help children interact and establish relationships with their peers. They can also fulfill their desires for possession by collecting items relating to their favorite characters. The purpose of acquiring an action figure or a comic character’s outfit is rarely about the object’s functionality but about bringing oneself into the world it represents by playing with it or wearing it.

Comics are popular and stimulate our desires for possession because we love and identify with the characters and their stories. Readers project their own experiences and thoughts onto characters such as the bright and courageous Chuke Ssu-langwith exemplary martial arts skills, Candy who represents adolescent girls longing for romantic love, and Hanamichi Sakuragi who transforms himself from a misbehaved teenager to an irreplaceable member of a basketball team. Reading comics is an extension of oneself, and sharing comics and comic merchandise with peers is both a form of social behavior and a search for identity. Whether officially licensed or pirated, whether of good or poor quality, a wide range of comic merchandise accompanies us through the ups and downs as we grow up and gives us courage.

Reference

Hung Te-lin, 2003, A Review of Comics in Taiwan, Taiwan Interminds Publishing

Chen Chung-wei, 2014, The Historical Records of Manga in Taiwan, Dowell Advertising

Chen Rou-jin, 2018, A Carpenter and His Taiwan Exposition, Rye Field Publishing

Yu Pei-yun, 2007, Children's Culture in Japanese Colonial Period Taiwan, Taiwan Interminds Publishing

About the Author

Wen Hsin-lin is a member of the National Comic Museum Preparatory Team at the National Museum of Taiwan History. Besides being a museum worker, she is also a hardcore comic fan. She has been going to Doujinshi conventions since she was in high school for around twenty years. She is currently exploring the possibilities of the upcoming National Comic Museum by combining her professional knowledge of museology and her experiences as a comic fan.

- Cheng Li-jung, 2015, “A Black Dog, My Family and Wartime Memories,” Kám-Á-Tiàm Forum of History

https://kamatiam.org/關於一隻黑狗與家族戰爭記憶/ (Viewed on Oct 5, 2021) - “Japanese Animated Film Classics,” National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

https://animation.filmarchives.jp/works/view/11105 - Private 1st Class Norakuro

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iV4piC5Cfq8 - Screening permit of Corporal Norakuro issued by the Education Bureau of Tainan Prefecture, collection of the National Museum of Taiwan History

https://collections.nmth.gov.tw/CollectionContent.aspx?a=132&rno=2005.001.0005 - Lee Cheng-liang, 2019, “Norainu Kurokichi, A Character Born out of A Lonely Teenager’s Imagination,” Taro News

https://taronews.tw/2019/01/17/225186/ (Viewed on Oct 9, 2021) - Norakuro Menko card, collection of the National Museum of Ethnology, Japan

http://htq2.minpaku.ac.jp/infolib/meta_pub/G0000028mofull_H0135090-0002 - Chang Yin-kun, 2016, “Can Toys Boost Morale? On the Fantastical and Adorable Qualities of Japanese Toys,” Streetcorner Sociology

https://twstreetcorner.org/2016/03/15/changyinkun/ (Viewed on Oct 10, 2021)